Trong hướng dẫn này, bạn sẽ học cách sử dụng Python với Redis (phát âm là RED-Iss, hoặc có thể là REE-diss hoặc Red-DEES, tùy thuộc vào người bạn yêu cầu), đây là một kho lưu trữ khóa-giá trị trong bộ nhớ nhanh như chớp. có thể được sử dụng cho mọi thứ từ A đến Z. Đây là nội dung của Bảy cơ sở dữ liệu trong bảy tuần , một cuốn sách nổi tiếng về cơ sở dữ liệu, phải nói về Redis:

Nó không chỉ đơn giản là dễ sử dụng; đó là một niềm vui. Nếu một API là UX cho các lập trình viên, thì Redis phải nằm trong Bảo tàng Nghệ thuật Hiện đại cùng với Mac Cube.

…

Và khi nói đến tốc độ, Redis rất khó bị đánh bại. Đọc nhanh và ghi thậm chí còn nhanh hơn, xử lý lên tới 100.000

SEThoạt động trên giây bởi một số điểm chuẩn. (Nguồn)

Có mưu đồ? Hướng dẫn này được xây dựng cho lập trình viên Python, những người có thể không có hoặc ít kinh nghiệm về Redis. Chúng tôi sẽ giải quyết hai công cụ cùng một lúc và giới thiệu cả bản thân Redis cũng như một trong các thư viện ứng dụng khách Python của nó, redis-py .

redis-py (mà bạn chỉ nhập dưới dạng redis ) là một trong nhiều ứng dụng khách Python cho Redis, nhưng nó có điểm khác biệt là được chính các nhà phát triển Redis lập hóa đơn là “hiện tại là cách để sử dụng Python”. Nó cho phép bạn gọi các lệnh Redis từ Python và đổi lại các đối tượng Python quen thuộc.

Trong hướng dẫn này, bạn sẽ trình bày :

- Cài đặt Redis từ nguồn và hiểu mục đích của các tệp nhị phân kết quả

- Học một phần nhỏ về Redis, bao gồm cú pháp, giao thức và thiết kế của nó

- Làm chủ

redis-pyđồng thời xem sơ qua về cách nó triển khai giao thức của Redis - Thiết lập và giao tiếp với phiên bản máy chủ Amazon ElastiCache Redis

Tải xuống miễn phí: Nhận một chương mẫu từ Thủ thuật Python:Cuốn sách chỉ cho bạn các phương pháp hay nhất của Python với các ví dụ đơn giản mà bạn có thể áp dụng ngay lập tức để viết mã + Pythonic đẹp hơn.

Cài đặt Redis Từ Nguồn

Như ông cố của tôi đã nói, không có gì xây dựng grit như cài đặt từ nguồn. Phần này sẽ hướng dẫn bạn tải xuống, tạo và cài đặt Redis. Tôi hứa rằng điều này sẽ không gây hại một chút nào!

Lưu ý :Phần này hướng tới cài đặt trên Mac OS X hoặc Linux. Nếu bạn đang sử dụng Windows, có một phiên bản Microsoft Redis có thể được cài đặt dưới dạng Dịch vụ Windows. Chỉ cần nói rằng Redis là một chương trình sống thoải mái nhất trên hộp Linux và việc thiết lập và sử dụng trên Windows có thể khó khăn.

Đầu tiên, hãy tải xuống mã nguồn Redis dưới dạng tarball:

$ redisurl="https://download.redis.io/redis-stable.tar.gz"

$ curl -s -o redis-stable.tar.gz $redisurl

Tiếp theo, chuyển sang root và giải nén mã nguồn của kho lưu trữ thành /usr/local/lib/ :

$ sudo su root

$ mkdir -p /usr/local/lib/

$ chmod a+w /usr/local/lib/

$ tar -C /usr/local/lib/ -xzf redis-stable.tar.gz

Theo tùy chọn, bây giờ bạn có thể xóa chính tệp lưu trữ:

$ rm redis-stable.tar.gz

Điều này sẽ để lại cho bạn một kho mã nguồn tại /usr/local/lib/redis-stable/ . Redis được viết bằng C, vì vậy bạn sẽ cần biên dịch, liên kết và cài đặt với make tiện ích:

$ cd /usr/local/lib/redis-stable/

$ make && make install

Sử dụng make install thực hiện hai hành động:

-

makeđầu tiên biên dịch lệnh và liên kết mã nguồn. -

make installpart lấy các mã nhị phân và sao chép chúng sang/usr/local/bin/để bạn có thể chạy chúng từ mọi nơi (giả sử rằng/usr/local/bin/nằm trongPATH).

Đây là tất cả các bước cho đến nay:

$ redisurl="https://download.redis.io/redis-stable.tar.gz"

$ curl -s -o redis-stable.tar.gz $redisurl

$ sudo su root

$ mkdir -p /usr/local/lib/

$ chmod a+w /usr/local/lib/

$ tar -C /usr/local/lib/ -xzf redis-stable.tar.gz

$ rm redis-stable.tar.gz

$ cd /usr/local/lib/redis-stable/

$ make && make install

Tại thời điểm này, hãy dành một chút thời gian để xác nhận rằng Redis nằm trong PATH của bạn và kiểm tra phiên bản của nó:

$ redis-cli --version

redis-cli 5.0.3

Nếu shell của bạn không tìm thấy redis-cli , hãy kiểm tra để đảm bảo rằng /usr/local/bin/ nằm trên PATH của bạn biến môi trường và thêm nó nếu không.

Ngoài redis-cli , make install thực sự dẫn đến một số ít các tệp thực thi khác nhau (và một liên kết tượng trưng) được đặt tại /usr/local/bin/ :

$ # A snapshot of executables that come bundled with Redis

$ ls -hFG /usr/local/bin/redis-* | sort

/usr/local/bin/redis-benchmark*

/usr/local/bin/redis-check-aof*

/usr/local/bin/redis-check-rdb*

/usr/local/bin/redis-cli*

/usr/local/bin/redis-sentinel@

/usr/local/bin/redis-server*

Mặc dù tất cả những thứ này đều có một số mục đích sử dụng, nhưng hai thứ mà bạn có thể sẽ quan tâm nhất là redis-cli và redis-server mà chúng tôi sẽ trình bày ngay sau đây. Nhưng trước khi chúng ta đi đến điều đó, việc thiết lập một số cấu hình cơ bản cần được thực hiện.

Định cấu hình Redis

Redis có cấu hình cao. Mặc dù nó hoạt động tốt, nhưng hãy dành một phút để đặt một số tùy chọn cấu hình đơn giản có liên quan đến tính bền vững của cơ sở dữ liệu và bảo mật cơ bản:

$ sudo su root

$ mkdir -p /etc/redis/

$ touch /etc/redis/6379.conf

Bây giờ, hãy viết nội dung sau vào /etc/redis/6379.conf . Chúng tôi sẽ trình bày dần dần ý nghĩa của hầu hết những điều này trong suốt hướng dẫn:

# /etc/redis/6379.conf

port 6379

daemonize yes

save 60 1

bind 127.0.0.1

tcp-keepalive 300

dbfilename dump.rdb

dir ./

rdbcompression yes

Cấu hình Redis tự lập tài liệu, với mẫu redis.conf tệp nằm trong nguồn Redis để bạn đọc vui vẻ. Nếu bạn đang sử dụng Redis trong một hệ thống sản xuất, thì việc chặn mọi phiền nhiễu và dành thời gian để đọc toàn bộ tệp mẫu này sẽ giúp bạn làm quen với các thông tin chi tiết của Redis và tinh chỉnh thiết lập của bạn.

Một số hướng dẫn, bao gồm các phần trong tài liệu của Redis, cũng có thể đề xuất chạy tập lệnh Shell install_server.sh nằm trong redis/utils/install_server.sh . Chúng tôi hoan nghênh bạn chạy phần mềm này như một giải pháp thay thế toàn diện hơn cho phần trên, nhưng hãy lưu ý một số điểm tốt hơn về install_server.sh :

- Nó sẽ không hoạt động trên Mac OS X — chỉ Debian và Ubuntu Linux.

- Nó sẽ đưa một bộ tùy chọn cấu hình đầy đủ hơn vào

/etc/redis/6379.conf. - Nó sẽ viết một System V

inittập lệnh thành/etc/init.d/redis_6379điều đó sẽ cho phép bạnsudo service redis_6379 start.

Hướng dẫn bắt đầu nhanh Redis cũng chứa một phần về cách thiết lập Redis phù hợp hơn, nhưng các tùy chọn cấu hình ở trên phải hoàn toàn đủ cho hướng dẫn này và bắt đầu.

Lưu ý bảo mật: Một vài năm trước, tác giả của Redis đã chỉ ra các lỗ hổng bảo mật trong các phiên bản Redis trước đó nếu không có cấu hình nào được thiết lập. Redis 3.2 (phiên bản 5.0.3 hiện tại kể từ tháng 3 năm 2019) đã thực hiện các bước để ngăn chặn sự xâm nhập này, đặt protected-mode tùy chọn yes theo mặc định.

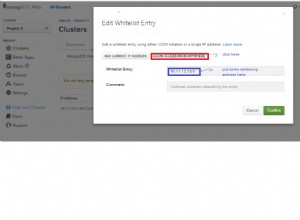

Chúng tôi đặt bind 127.0.0.1 một cách rõ ràng để cho phép Redis chỉ lắng nghe các kết nối từ giao diện máy chủ cục bộ, mặc dù bạn sẽ cần mở rộng danh sách trắng này trong một máy chủ sản xuất thực. Điểm của protected-mode là một biện pháp bảo vệ sẽ bắt chước hành vi liên kết với máy chủ cục bộ này nếu bạn không chỉ định bất kỳ điều gì trong bind tùy chọn.

Với bình phương đó, giờ đây chúng ta có thể tìm hiểu cách sử dụng chính Redis.

Còn 10 phút nữa là xong

Phần này sẽ cung cấp cho bạn kiến thức vừa đủ về Redis nguy hiểm, nêu rõ thiết kế và cách sử dụng cơ bản của nó.

Bắt đầu

Redis có kiến trúc máy khách-máy chủ và sử dụng mô hình phản hồi yêu cầu . Điều này có nghĩa là bạn (máy khách) kết nối với máy chủ Redis thông qua kết nối TCP, trên cổng 6379 theo mặc định. Bạn yêu cầu một số hành động (như một số hình thức đọc, ghi, tải, cài đặt hoặc cập nhật) và máy chủ phục vụ bạn trả lời phản hồi.

Có thể có nhiều máy khách nói chuyện với cùng một máy chủ, đó thực sự là những gì Redis hoặc bất kỳ ứng dụng máy chủ-máy khách nào đều hướng tới. Mỗi máy khách thực hiện một (thường là chặn) đọc trên một ổ cắm để chờ phản hồi của máy chủ.

cli trong redis-cli là viết tắt của giao diện dòng lệnh và máy chủ server trong redis-server là để chạy một máy chủ. Theo cùng một cách mà bạn sẽ chạy python tại dòng lệnh, bạn có thể chạy redis-cli để chuyển sang REPL tương tác (Read Eval Print Loop) nơi bạn có thể chạy các lệnh máy khách trực tiếp từ shell.

Tuy nhiên, trước tiên, bạn cần khởi chạy redis-server để bạn có một máy chủ Redis đang chạy để nói chuyện. Một cách phổ biến để thực hiện việc này trong quá trình phát triển là khởi động một máy chủ tại localhost (địa chỉ IPv4 127.0.0.1 ), là mặc định trừ khi bạn nói với Redis bằng cách khác. Bạn cũng có thể chuyển redis-server tên của tệp cấu hình của bạn, giống với việc chỉ định tất cả các cặp khóa-giá trị của nó dưới dạng đối số dòng lệnh:

$ redis-server /etc/redis/6379.conf

31829:C 07 Mar 2019 08:45:04.030 # oO0OoO0OoO0Oo Redis is starting oO0OoO0OoO0Oo

31829:C 07 Mar 2019 08:45:04.030 # Redis version=5.0.3, bits=64, commit=00000000, modified=0, pid=31829, just started

31829:C 07 Mar 2019 08:45:04.030 # Configuration loaded

Chúng tôi đặt daemonize tùy chọn cấu hình thành yes , do đó máy chủ chạy ở chế độ nền. (Nếu không, hãy sử dụng --daemonize yes như một tùy chọn cho redis-server .)

Bây giờ bạn đã sẵn sàng khởi chạy Redis REPL. Nhập redis-cli trên dòng lệnh của bạn. Bạn sẽ thấy máy chủ:cổng của máy chủ theo sau là một cặp > lời nhắc:

127.0.0.1:6379>

Đây là một trong những lệnh Redis đơn giản nhất, PING , chỉ kiểm tra kết nối với máy chủ và trả về "PONG" nếu mọi thứ ổn:

127.0.0.1:6379> PING

PONG

Các lệnh Redis không phân biệt chữ hoa chữ thường, mặc dù các lệnh Python của chúng chắc chắn là không.

Lưu ý: Như một kiểm tra tỉnh táo khác, bạn có thể tìm kiếm ID quy trình của máy chủ Redis bằng pgrep :

$ pgrep redis-server

26983

Để tắt máy chủ, hãy sử dụng pkill redis-server từ dòng lệnh. Trên Mac OS X, bạn cũng có thể sử dụng redis-cli shutdown .

Tiếp theo, chúng tôi sẽ sử dụng một số lệnh Redis phổ biến và so sánh chúng với giao diện của chúng trong Python thuần túy.

Redis as a Python Dictionary

Redis là viết tắt của Dịch vụ từ điển từ xa .

"Ý bạn là, giống như một từ điển Python?" bạn có thể hỏi.

Đúng. Nói chung, có rất nhiều điểm tương đồng mà bạn có thể rút ra giữa từ điển Python (hoặc bảng băm chung) và Redis là gì và làm gì:

-

Cơ sở dữ liệu Redis giữ key:value ghép nối và hỗ trợ các lệnh như

GET,SETvàDEL, cũng như hàng trăm lệnh bổ sung. -

Redis phím luôn là chuỗi.

-

Redis giá trị có thể là một số kiểu dữ liệu khác nhau. Chúng tôi sẽ đề cập đến một số kiểu dữ liệu giá trị quan trọng hơn trong hướng dẫn này:

string,list,hashesvàsets. Một số loại nâng cao bao gồm các mục không gian địa lý và loại luồng mới. -

Nhiều lệnh Redis hoạt động trong thời gian O (1) không đổi, giống như truy xuất giá trị từ

dicttrong Python hoặc bất kỳ bảng băm nào.

Người tạo ra Redis, Salvatore Sanfilippo có lẽ sẽ không thích việc so sánh cơ sở dữ liệu Redis với một dict Python đơn giản . Anh ấy gọi dự án là “máy chủ cấu trúc dữ liệu” (chứ không phải là nơi lưu trữ khóa-giá trị, chẳng hạn như memcached) bởi vì theo tín dụng của nó, Redis hỗ trợ lưu trữ các loại bổ sung của key:value các kiểu dữ liệu ngoài string:string . Nhưng đối với mục đích của chúng tôi ở đây, đó là một so sánh hữu ích nếu bạn đã quen thuộc với đối tượng từ điển của Python.

Hãy bắt đầu và tìm hiểu bằng ví dụ. Cơ sở dữ liệu đồ chơi đầu tiên của chúng tôi (với ID 0) sẽ là bản đồ của country:capital city , nơi chúng tôi sử dụng SET để đặt các cặp khóa-giá trị:

127.0.0.1:6379> SET Bahamas Nassau

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> SET Croatia Zagreb

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> GET Croatia

"Zagreb"

127.0.0.1:6379> GET Japan

(nil)

Chuỗi các câu lệnh tương ứng trong Python thuần túy sẽ có dạng như sau:

>>>>>> capitals = {}

>>> capitals["Bahamas"] = "Nassau"

>>> capitals["Croatia"] = "Zagreb"

>>> capitals.get("Croatia")

'Zagreb'

>>> capitals.get("Japan") # None

Chúng tôi sử dụng capitals.get("Japan") thay vì capitals["Japan"] vì Redis sẽ trả về nil chứ không phải là lỗi khi không tìm thấy khóa, tương tự như None của Python .

Redis cũng cho phép bạn đặt và nhận nhiều cặp khóa-giá trị trong một lệnh, MSET và MGET , tương ứng:

127.0.0.1:6379> MSET Lebanon Beirut Norway Oslo France Paris

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> MGET Lebanon Norway Bahamas

1) "Beirut"

2) "Oslo"

3) "Nassau"

Điều gần nhất trong Python là với dict.update() :

>>> capitals.update({

... "Lebanon": "Beirut",

... "Norway": "Oslo",

... "France": "Paris",

... })

>>> [capitals.get(k) for k in ("Lebanon", "Norway", "Bahamas")]

['Beirut', 'Oslo', 'Nassau']

Chúng tôi sử dụng .get() thay vì .__getitem__() để bắt chước hành vi của Redis là trả về giá trị giống null khi không tìm thấy khóa nào.

Ví dụ thứ ba, EXISTS lệnh thực hiện những gì nó giống như âm thanh, đó là để kiểm tra xem một khóa có tồn tại hay không:

127.0.0.1:6379> EXISTS Norway

(integer) 1

127.0.0.1:6379> EXISTS Sweden

(integer) 0

Python có in từ khóa để kiểm tra điều tương tự, định tuyến nào đến dict.__contains__(key) :

>>> "Norway" in capitals

True

>>> "Sweden" in capitals

False

Một vài ví dụ này nhằm hiển thị, sử dụng Python bản địa, những gì đang xảy ra ở cấp độ cao với một vài lệnh Redis phổ biến. Không có thành phần máy chủ-máy khách nào ở đây đối với các ví dụ Python và redis-py vẫn chưa vào hình. Ví dụ, điều này chỉ nhằm hiển thị chức năng của Redis.

Dưới đây là tóm tắt về một số lệnh Redis mà bạn đã thấy và các lệnh Python chức năng tương đương của chúng:

capitals["Bahamas"] = "Nassau"

capitals.get("Croatia")

capitals.update(

{

"Lebanon": "Beirut",

"Norway": "Oslo",

"France": "Paris",

}

)

[capitals[k] for k in ("Lebanon", "Norway", "Bahamas")]

"Norway" in capitals

Thư viện ứng dụng Python Redis, redis-py , mà bạn sẽ đi sâu vào ngay trong bài viết này, mọi thứ sẽ khác. Nó đóng gói một kết nối TCP thực với máy chủ Redis và gửi các lệnh thô, dưới dạng byte được tuần tự hóa bằng Giao thức tuần tự hóa REdis (RESP), đến máy chủ. Sau đó, nó nhận câu trả lời thô và phân tích cú pháp nó trở lại thành một đối tượng Python chẳng hạn như bytes , int hoặc thậm chí datetime.datetime .

Lưu ý :Cho đến nay, bạn đã nói chuyện với máy chủ Redis thông qua redis-cli tương tác TRẢ LỜI. Bạn cũng có thể ra lệnh trực tiếp, giống như cách bạn chuyển tên của tập lệnh vào python có thể thực thi, chẳng hạn như python myscript.py .

Cho đến nay, bạn đã thấy một số kiểu dữ liệu cơ bản của Redis, là một ánh xạ của string:string . Mặc dù cặp khóa-giá trị này phổ biến ở hầu hết các cửa hàng khóa-giá trị, nhưng Redis cung cấp một số loại giá trị có thể có khác mà bạn sẽ thấy tiếp theo.

Các kiểu dữ liệu khác trong Python so với Redis

Trước khi bạn kích hoạt redis-py Ứng dụng khách Python, nó cũng giúp bạn nắm bắt cơ bản về một vài kiểu dữ liệu Redis khác. Để rõ ràng, tất cả các phím Redis đều là chuỗi. Đó là giá trị có thể nhận các kiểu dữ liệu (hoặc cấu trúc) ngoài các giá trị chuỗi được sử dụng trong các ví dụ cho đến nay.

A băm là một ánh xạ của string:string , được gọi là trường-giá trị các cặp nằm dưới một khóa cấp cao nhất:

127.0.0.1:6379> HSET realpython url "https://realpython.com/"

(integer) 1

127.0.0.1:6379> HSET realpython github realpython

(integer) 1

127.0.0.1:6379> HSET realpython fullname "Real Python"

(integer) 1

Điều này đặt ba cặp giá trị trường cho một khóa , "realpython" . Nếu bạn đã quen với các thuật ngữ và đối tượng của Python, điều này có thể gây nhầm lẫn. Hàm băm Redis gần giống với một dict trong Python được lồng vào sâu một cấp:

data = {

"realpython": {

"url": "https://realpython.com/",

"github": "realpython",

"fullname": "Real Python",

}

}

Các trường của Redis tương tự như các khóa Python của mỗi cặp khóa-giá trị lồng nhau trong từ điển bên trong ở trên. Redis bảo lưu thuật ngữ khóa cho khóa cơ sở dữ liệu cấp cao nhất chứa chính cấu trúc băm.

Cũng giống như có MSET cho string:string cơ bản các cặp khóa-giá trị, còn có HMSET cho băm để đặt nhiều cặp trong đối tượng giá trị băm:

127.0.0.1:6379> HMSET pypa url "https://www.pypa.io/" github pypa fullname "Python Packaging Authority"

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> HGETALL pypa

1) "url"

2) "https://www.pypa.io/"

3) "github"

4) "pypa"

5) "fullname"

6) "Python Packaging Authority"

Sử dụng HMSET có lẽ là cách song song gần gũi hơn với cách chúng tôi đã gán data vào một từ điển lồng nhau ở trên, thay vì đặt từng cặp lồng nhau như được thực hiện với HSET .

Hai loại giá trị bổ sung là danh sách và bộ , có thể thay thế hàm băm hoặc chuỗi dưới dạng giá trị Redis. Chúng phần lớn giống như âm thanh của chúng, vì vậy tôi sẽ không làm mất thời gian của bạn với các ví dụ bổ sung. Mỗi hàm băm, danh sách và bộ đều có một số lệnh cụ thể cho kiểu dữ liệu nhất định đó, trong một số trường hợp, chúng được biểu thị bằng chữ cái đầu của chúng:

-

Hàm băm: Các lệnh hoạt động trên hàm băm bắt đầu bằng

H, chẳng hạn nhưHSET,HGEThoặcHMSET. -

Bộ: Các lệnh hoạt động trên bộ bắt đầu bằng

S, chẳng hạn nhưSCARD, nhận số phần tử ở giá trị đã đặt tương ứng với một khóa nhất định. -

Danh sách: Các lệnh hoạt động trên danh sách bắt đầu bằng

LhoặcR. Các ví dụ bao gồmLPOPvàRPUSH.LhoặcRđề cập đến mặt nào của danh sách được vận hành. Một số lệnh danh sách cũng được mở đầu bằngB, có nghĩa là chặn . Một hoạt động chặn không để các hoạt động khác làm gián đoạn nó trong khi nó đang thực thi. Ví dụ:BLPOPthực hiện một cửa sổ bật lên bên trái chặn trên cấu trúc danh sách.

Lưu ý: Một tính năng đáng chú ý của kiểu danh sách của Redis là nó là một danh sách được liên kết chứ không phải là một mảng. Điều này có nghĩa là thêm vào là O (1) trong khi lập chỉ mục ở một số chỉ mục tùy ý là O (N).

Dưới đây là danh sách nhanh các lệnh dành riêng cho các kiểu dữ liệu chuỗi, băm, danh sách và thiết lập trong Redis:

| Loại | Lệnh |

|---|---|

| Bộ | SADD , SCARD , SDIFF , SDIFFSTORE , SINTER , SINTERSTORE , SISMEMBER , SMEMBERS , SMOVE , SPOP , SRANDMEMBER , SREM , SSCAN , SUNION , SUNIONSTORE |

| Hàm băm | HDEL , HEXISTS , HGET , HGETALL , HINCRBY , HINCRBYFLOAT , HKEYS , HLEN , HMGET , HMSET , HSCAN , HSET , HSETNX , HSTRLEN , HVALS |

| Danh sách | BLPOP , BRPOP , BRPOPLPUSH , LINDEX , LINSERT , LLEN , LPOP , LPUSH , LPUSHX , LRANGE , LREM , LSET , LTRIM , RPOP , RPOPLPUSH , RPUSH , RPUSHX |

| Chuỗi | APPEND , BITCOUNT , BITFIELD , BITOP , BITPOS , DECR , DECRBY , GET , GETBIT , GETRANGE , GET , INCR , INCRBY , INCRBYFLOAT , MGET , MSET , MSETNX , PSETEX , SET , SETBIT , SETEX , SETNX , SETRANGE , STRLEN |

Bảng này không phải là bức tranh hoàn chỉnh về các loại và lệnh của Redis. Có một loạt các loại dữ liệu nâng cao hơn, chẳng hạn như các mục không gian địa lý, tập hợp được sắp xếp và HyperLogLog. Tại trang lệnh Redis, bạn có thể lọc theo nhóm cấu trúc dữ liệu. Ngoài ra còn có phần tóm tắt các loại dữ liệu và giới thiệu về các loại dữ liệu Redis.

Vì chúng ta sẽ chuyển sang làm mọi thứ bằng Python, nên bây giờ bạn có thể xóa cơ sở dữ liệu đồ chơi của mình bằng FLUSHDB và thoát khỏi redis-cli TRẢ LỜI:

127.0.0.1:6379> FLUSHDB

OK

127.0.0.1:6379> QUIT

Điều này sẽ đưa bạn trở lại lời nhắc trình bao của bạn. Bạn có thể rời khỏi redis-server chạy trong nền, vì bạn cũng sẽ cần nó cho phần còn lại của hướng dẫn.

Sử dụng redis-py :Redis bằng Python

Bây giờ bạn đã thành thạo một số kiến thức cơ bản về Redis, đã đến lúc chuyển sang redis-py , ứng dụng khách Python cho phép bạn nói chuyện với Redis từ API Python thân thiện với người dùng.

Các bước đầu tiên

redis-py là một thư viện máy khách Python được thiết lập tốt cho phép bạn nói chuyện trực tiếp với máy chủ Redis thông qua các lệnh gọi Python:

$ python -m pip install redis

Tiếp theo, hãy đảm bảo rằng máy chủ Redis của bạn vẫn đang hoạt động trong nền. Bạn có thể kiểm tra bằng pgrep redis-server và nếu bạn đến tay không, hãy khởi động lại máy chủ cục bộ với redis-server /etc/redis/6379.conf .

Bây giờ, hãy đi vào phần trọng tâm của Python. Đây là “hello world” của redis-py :

1>>> import redis

2>>> r = redis.Redis()

3>>> r.mset({"Croatia": "Zagreb", "Bahamas": "Nassau"})

4True

5>>> r.get("Bahamas")

6b'Nassau'

Redis , được sử dụng trong Dòng 2, là lớp trung tâm của gói và là workhorse mà bạn thực thi (hầu như) bất kỳ lệnh Redis nào. Kết nối và sử dụng lại socket TCP được thực hiện cho bạn đằng sau hậu trường và bạn gọi các lệnh Redis bằng cách sử dụng các phương thức trên cá thể lớp r .

Cũng lưu ý rằng loại đối tượng được trả về, b'Nassau' trong Dòng 6, là bytes của Python nhập, không phải str . Nó là bytes chứ không phải là str đó là kiểu trả về phổ biến nhất trên redis-py , vì vậy bạn có thể cần gọi r.get("Bahamas").decode("utf-8") tùy thuộc vào những gì bạn muốn thực sự làm với bytestring trả về.

Đoạn mã trên có quen thuộc không? Các phương thức trong hầu hết các trường hợp đều khớp với tên của lệnh Redis có tác dụng tương tự. Tại đây, bạn đã gọi r.mset() và r.get() , tương ứng với MSET và GET trong API Redis gốc.

Điều này cũng có nghĩa là HGETALL trở thành r.hgetall() , PING trở thành r.ping() , và như thế. Có một vài ngoại lệ, nhưng quy tắc này phù hợp với phần lớn các lệnh.

Trong khi các đối số lệnh Redis thường chuyển thành một chữ ký phương thức trông giống nhau, chúng lấy các đối tượng Python. Ví dụ:lệnh gọi tới r.mset() trong ví dụ trên sử dụng một Python dict là đối số đầu tiên của nó, thay vì một chuỗi các byte.

Chúng tôi đã xây dựng Redis phiên bản r không có đối số, nhưng nó đi kèm với một số tham số nếu bạn cần:

# From redis/client.py

class Redis(object):

def __init__(self, host='localhost', port=6379,

db=0, password=None, socket_timeout=None,

# ...

Bạn có thể thấy rằng tên máy chủ:cổng mặc định cặp là localhost:6379 , đó là chính xác những gì chúng tôi cần trong trường hợp redis-server được lưu giữ cục bộ của chúng tôi ví dụ.

db tham số là số cơ sở dữ liệu. Bạn có thể quản lý nhiều cơ sở dữ liệu trong Redis cùng một lúc và mỗi cơ sở dữ liệu được xác định bằng một số nguyên. Theo mặc định, số lượng cơ sở dữ liệu tối đa là 16.

Khi bạn chỉ chạy redis-cli từ dòng lệnh, điều này sẽ bắt đầu bạn ở cơ sở dữ liệu 0. Sử dụng -n cờ để bắt đầu một cơ sở dữ liệu mới, như trong redis-cli -n 5 .

Các loại khóa được phép

Một điều đáng biết là redis-py yêu cầu bạn chuyển nó các khóa bytes , str , int hoặc float . (Nó sẽ chuyển đổi 3 loại cuối cùng trong số này thành bytes trước khi gửi chúng đến máy chủ.)

Hãy xem xét trường hợp bạn muốn sử dụng ngày lịch làm khóa:

>>>>>> import datetime

>>> today = datetime.date.today()

>>> visitors = {"dan", "jon", "alex"}

>>> r.sadd(today, *visitors)

Traceback (most recent call last):

# ...

redis.exceptions.DataError: Invalid input of type: 'date'.

Convert to a byte, string or number first.

Bạn sẽ cần chuyển đổi rõ ràng date trong Python đối tượng với str , bạn có thể thực hiện với .isoformat() :

>>> stoday = today.isoformat() # Python 3.7+, or use str(today)

>>> stoday

'2019-03-10'

>>> r.sadd(stoday, *visitors) # sadd: set-add

3

>>> r.smembers(stoday)

{b'dan', b'alex', b'jon'}

>>> r.scard(today.isoformat())

3

Tóm lại, bản thân Redis chỉ cho phép chuỗi làm phím. redis-py tự do hơn một chút về loại Python mà nó sẽ chấp nhận, mặc dù cuối cùng nó chuyển đổi mọi thứ thành byte trước khi gửi chúng đến máy chủ Redis.

Ví dụ:PyHats.com

Đã đến lúc tìm ra một ví dụ đầy đủ hơn. Giả sử chúng ta quyết định thành lập một trang web sinh lợi, PyHats.com, bán những chiếc mũ đắt quá mức cho bất kỳ ai sẽ mua chúng và thuê bạn xây dựng trang web.

Bạn sẽ sử dụng Redis để xử lý một số danh mục sản phẩm, kiểm kê và phát hiện lưu lượng truy cập bot cho PyHats.com.

Đây là ngày đầu tiên của trang web và chúng tôi sẽ bán ba chiếc mũ phiên bản giới hạn. Mỗi chiếc mũ được giữ trong một hàm băm Redis của các cặp giá trị trường và hàm băm có một khóa là một số nguyên ngẫu nhiên có tiền tố, chẳng hạn như hat:56854717 . Sử dụng hat: tiền tố là quy ước Redis để tạo một loại không gian tên trong cơ sở dữ liệu Redis:

import random

random.seed(444)

hats = {f"hat:{random.getrandbits(32)}": i for i in (

{

"color": "black",

"price": 49.99,

"style": "fitted",

"quantity": 1000,

"npurchased": 0,

},

{

"color": "maroon",

"price": 59.99,

"style": "hipster",

"quantity": 500,

"npurchased": 0,

},

{

"color": "green",

"price": 99.99,

"style": "baseball",

"quantity": 200,

"npurchased": 0,

})

}

Hãy bắt đầu với cơ sở dữ liệu 1 vì chúng tôi đã sử dụng cơ sở dữ liệu 0 trong một ví dụ trước:

>>> r = redis.Redis(db=1)

Để ghi lần đầu dữ liệu này vào Redis, chúng ta có thể sử dụng .hmset() (băm nhiều bộ), gọi nó cho từng từ điển. “Multi” là tham chiếu đến việc đặt nhiều cặp trường-giá trị, trong đó “trường” trong trường hợp này tương ứng với một khóa của bất kỳ từ điển nào được lồng trong hats :

1>>> with r.pipeline() as pipe:

2... for h_id, hat in hats.items():

3... pipe.hmset(h_id, hat)

4... pipe.execute()

5Pipeline<ConnectionPool<Connection<host=localhost,port=6379,db=1>>>

6Pipeline<ConnectionPool<Connection<host=localhost,port=6379,db=1>>>

7Pipeline<ConnectionPool<Connection<host=localhost,port=6379,db=1>>>

8[True, True, True]

9

10>>> r.bgsave()

11True

Khối mã ở trên cũng giới thiệu khái niệm về Redis pipelining , đó là một cách để cắt giảm số lượng giao dịch khứ hồi mà bạn cần ghi hoặc đọc dữ liệu từ máy chủ Redis của mình. Nếu bạn vừa gọi r.hmset() ba lần, sau đó điều này sẽ yêu cầu một hoạt động khứ hồi qua lại cho mỗi hàng được viết.

Với một đường ống dẫn, tất cả các lệnh được lưu vào bộ đệm ở phía máy khách và sau đó được gửi cùng một lúc, trong một lần rơi xuống, sử dụng pipe.hmset() trong Dòng 3. Đây là lý do tại sao ba True tất cả các câu trả lời đều được trả lại cùng một lúc, khi bạn gọi pipe.execute() trong Dòng 4. Bạn sẽ sớm thấy một trường hợp sử dụng nâng cao hơn cho một đường dẫn.

Lưu ý :Tài liệu của Redis cung cấp một ví dụ về việc thực hiện điều này tương tự với redis-cli , nơi bạn có thể chuyển nội dung của một tệp cục bộ để thực hiện việc chèn hàng loạt.

Hãy kiểm tra nhanh xem mọi thứ đều có trong cơ sở dữ liệu Redis của chúng tôi:

>>>>>> pprint(r.hgetall("hat:56854717"))

{b'color': b'green',

b'npurchased': b'0',

b'price': b'99.99',

b'quantity': b'200',

b'style': b'baseball'}

>>> r.keys() # Careful on a big DB. keys() is O(N)

[b'56854717', b'1236154736', b'1326692461']

Điều đầu tiên mà chúng tôi muốn mô phỏng là điều gì sẽ xảy ra khi người dùng nhấp vào Mua hàng . Nếu mặt hàng còn trong kho, hãy tăng npurchased của nó 1 và giảm quantity (khoảng không quảng cáo) bằng 1. Bạn có thể sử dụng .hincrby() để làm điều này:

>>> r.hincrby("hat:56854717", "quantity", -1)

199

>>> r.hget("hat:56854717", "quantity")

b'199'

>>> r.hincrby("hat:56854717", "npurchased", 1)

1

Lưu ý :HINCRBY vẫn hoạt động trên một giá trị băm là một chuỗi, nhưng nó cố gắng diễn giải chuỗi đó là một số nguyên có dấu 64-bit cơ sở 10 để thực hiện thao tác.

Điều này áp dụng cho các lệnh khác liên quan đến tăng và giảm cho các cấu trúc dữ liệu khác, cụ thể là INCR , INCRBY , INCRBYFLOAT , ZINCRBY và HINCRBYFLOAT . Bạn sẽ gặp lỗi nếu chuỗi ở giá trị không thể được biểu diễn dưới dạng số nguyên.

Tuy nhiên, nó không thực sự đơn giản như vậy. Thay đổi quantity và npurchased trong hai dòng mã ẩn thực tế rằng một nhấp chuột, mua hàng và thanh toán đòi hỏi nhiều hơn thế. Chúng tôi cần kiểm tra thêm một số lần nữa để đảm bảo không để ai đó mang ví nhẹ hơn và không đội mũ:

- Bước 1: Check if the item is in stock, or otherwise raise an exception on the backend.

- Step 2: If it is in stock, then execute the transaction, decrease the

quantityfield, and increase thenpurchasedlĩnh vực này. - Step 3: Be alert for any changes that alter the inventory in between the first two steps (a race condition).

Step 1 is relatively straightforward:it consists of an .hget() to check the available quantity.

Step 2 is a little bit more involved. The pair of increase and decrease operations need to be executed atomically :either both should be completed successfully, or neither should be (in the case that at least one fails).

With client-server frameworks, it’s always crucial to pay attention to atomicity and look out for what could go wrong in instances where multiple clients are trying to talk to the server at once. The answer to this in Redis is to use a transaction block, meaning that either both or neither of the commands get through.

In redis-py , Pipeline is a transactional pipeline class by default. This means that, even though the class is actually named for something else (pipelining), it can be used to create a transaction block also.

In Redis, a transaction starts with MULTI and ends with EXEC :

1127.0.0.1:6379> MULTI

2127.0.0.1:6379> HINCRBY 56854717 quantity -1

3127.0.0.1:6379> HINCRBY 56854717 npurchased 1

4127.0.0.1:6379> EXEC

MULTI (Line 1) marks the start of the transaction, and EXEC (Line 4) marks the end. Everything in between is executed as one all-or-nothing buffered sequence of commands. This means that it will be impossible to decrement quantity (Line 2) but then have the balancing npurchased increment operation fail (Line 3).

Let’s circle back to Step 3:we need to be aware of any changes that alter the inventory in between the first two steps.

Step 3 is the trickiest. Let’s say that there is one lone hat remaining in our inventory. In between the time that User A checks the quantity of hats remaining and actually processes their transaction, User B also checks the inventory and finds likewise that there is one hat listed in stock. Both users will be allowed to purchase the hat, but we have 1 hat to sell, not 2, so we’re on the hook and one user is out of their money. Not good.

Redis has a clever answer for the dilemma in Step 3:it’s called optimistic locking , and is different than how typical locking works in an RDBMS such as PostgreSQL. Optimistic locking, in a nutshell, means that the calling function (client) does not acquire a lock, but rather monitors for changes in the data it is writing to during the time it would have held a lock . If there’s a conflict during that time, the calling function simply tries the whole process again.

You can effect optimistic locking by using the WATCH command (.watch() in redis-py ), which provides a check-and-set behavior.

Let’s introduce a big chunk of code and walk through it afterwards step by step. You can picture buyitem() as being called any time a user clicks on a Buy Now or Purchase button. Its purpose is to confirm the item is in stock and take an action based on that result, all in a safe manner that looks out for race conditions and retries if one is detected:

1import logging

2import redis

3

4logging.basicConfig()

5

6class OutOfStockError(Exception):

7 """Raised when PyHats.com is all out of today's hottest hat"""

8

9def buyitem(r: redis.Redis, itemid: int) -> None:

10 with r.pipeline() as pipe:

11 error_count = 0

12 while True:

13 try:

14 # Get available inventory, watching for changes

15 # related to this itemid before the transaction

16 pipe.watch(itemid)

17 nleft: bytes = r.hget(itemid, "quantity")

18 if nleft > b"0":

19 pipe.multi()

20 pipe.hincrby(itemid, "quantity", -1)

21 pipe.hincrby(itemid, "npurchased", 1)

22 pipe.execute()

23 break

24 else:

25 # Stop watching the itemid and raise to break out

26 pipe.unwatch()

27 raise OutOfStockError(

28 f"Sorry, {itemid} is out of stock!"

29 )

30 except redis.WatchError:

31 # Log total num. of errors by this user to buy this item,

32 # then try the same process again of WATCH/HGET/MULTI/EXEC

33 error_count += 1

34 logging.warning(

35 "WatchError #%d: %s; retrying",

36 error_count, itemid

37 )

38 return None

The critical line occurs at Line 16 with pipe.watch(itemid) , which tells Redis to monitor the given itemid for any changes to its value. The program checks the inventory through the call to r.hget(itemid, "quantity") , in Line 17:

16pipe.watch(itemid)

17nleft: bytes = r.hget(itemid, "quantity")

18if nleft > b"0":

19 # Item in stock. Proceed with transaction.

If the inventory gets touched during this short window between when the user checks the item stock and tries to purchase it, then Redis will return an error, and redis-py will raise a WatchError (Line 30). That is, if any of the hash pointed to by itemid changes after the .hget() call but before the subsequent .hincrby() calls in Lines 20 and 21, then we’ll re-run the whole process in another iteration of the while True loop as a result.

This is the “optimistic” part of the locking:rather than letting the client have a time-consuming total lock on the database through the getting and setting operations, we leave it up to Redis to notify the client and user only in the case that calls for a retry of the inventory check.

One key here is in understanding the difference between client-side and server-side hoạt động:

nleft = r.hget(itemid, "quantity")

This Python assignment brings the result of r.hget() client-side. Conversely, methods that you call on pipe effectively buffer all of the commands into one, and then send them to the server in a single request:

16pipe.multi()

17pipe.hincrby(itemid, "quantity", -1)

18pipe.hincrby(itemid, "npurchased", 1)

19pipe.execute()

No data comes back to the client side in the middle of the transactional pipeline. You need to call .execute() (Line 19) to get the sequence of results back all at once.

Even though this block contains two commands, it consists of exactly one round-trip operation from client to server and back.

This means that the client can’t immediately use the result of pipe.hincrby(itemid, "quantity", -1) , from Line 20, because methods on a Pipeline return just the pipe instance itself. We haven’t asked anything from the server at this point. While normally .hincrby() returns the resulting value, you can’t immediately reference it on the client side until the entire transaction is completed.

There’s a catch-22:this is also why you can’t put the call to .hget() into the transaction block. If you did this, then you’d be unable to know if you want to increment the npurchased field yet, since you can’t get real-time results from commands that are inserted into a transactional pipeline.

Finally, if the inventory sits at zero, then we UNWATCH the item ID and raise an OutOfStockError (Line 27), ultimately displaying that coveted Sold Out page that will make our hat buyers desperately want to buy even more of our hats at ever more outlandish prices:

24else:

25 # Stop watching the itemid and raise to break out

26 pipe.unwatch()

27 raise OutOfStockError(

28 f"Sorry, {itemid} is out of stock!"

29 )

Here’s an illustration. Keep in mind that our starting quantity is 199 for hat 56854717 since we called .hincrby() bên trên. Let’s mimic 3 purchases, which should modify the quantity and npurchased lĩnh vực:

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> r.hmget("hat:56854717", "quantity", "npurchased") # Hash multi-get

[b'196', b'4']

Now, we can fast-forward through more purchases, mimicking a stream of purchases until the stock depletes to zero. Again, picture these coming from a whole bunch of different clients rather than just one Redis ví dụ:

>>> # Buy remaining 196 hats for item 56854717 and deplete stock to 0

>>> for _ in range(196):

... buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

>>> r.hmget("hat:56854717", "quantity", "npurchased")

[b'0', b'200']

Now, when some poor user is late to the game, they should be met with an OutOfStockError that tells our application to render an error message page on the frontend:

>>> buyitem(r, "hat:56854717")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 20, in buyitem

__main__.OutOfStockError: Sorry, hat:56854717 is out of stock!

Looks like it’s time to restock.

Using Key Expiry

Let’s introduce key expiry , which is another distinguishing feature in Redis. When you expire a key, that key and its corresponding value will be automatically deleted from the database after a certain number of seconds or at a certain timestamp.

In redis-py , one way that you can accomplish this is through .setex() , which lets you set a basic string:string key-value pair with an expiration:

1>>> from datetime import timedelta

2

3>>> # setex: "SET" with expiration

4>>> r.setex(

5... "runner",

6... timedelta(minutes=1),

7... value="now you see me, now you don't"

8... )

9True

You can specify the second argument as a number in seconds or a timedelta object, as in Line 6 above. I like the latter because it seems less ambiguous and more deliberate.

There are also methods (and corresponding Redis commands, of course) to get the remaining lifetime (time-to-live ) of a key that you’ve set to expire:

>>>>>> r.ttl("runner") # "Time To Live", in seconds

58

>>> r.pttl("runner") # Like ttl, but milliseconds

54368

Below, you can accelerate the window until expiration, and then watch the key expire, after which r.get() will return None and .exists() will return 0 :

>>> r.get("runner") # Not expired yet

b"now you see me, now you don't"

>>> r.expire("runner", timedelta(seconds=3)) # Set new expire window

True

>>> # Pause for a few seconds

>>> r.get("runner")

>>> r.exists("runner") # Key & value are both gone (expired)

0

The table below summarizes commands related to key-value expiration, including the ones covered above. The explanations are taken directly from redis-py method docstrings:

| Signature | Purpose |

|---|---|

r.setex(name, time, value) | Sets the value of key name to value that expires in time seconds, where time can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.psetex(name, time_ms, value) | Sets the value of key name to value that expires in time_ms milliseconds, where time_ms can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.expire(name, time) | Sets an expire flag on key name for time seconds, where time can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.expireat(name, when) | Sets an expire flag on key name , where when can be represented as an int indicating Unix time or a Python datetime object |

r.persist(name) | Removes an expiration on name |

r.pexpire(name, time) | Sets an expire flag on key name for time milliseconds, and time can be represented by an int or a Python timedelta object |

r.pexpireat(name, when) | Sets an expire flag on key name , where when can be represented as an int representing Unix time in milliseconds (Unix time * 1000) or a Python datetime object |

r.pttl(name) | Returns the number of milliseconds until the key name will expire |

r.ttl(name) | Returns the number of seconds until the key name will expire |

PyHats.com, Part 2

A few days after its debut, PyHats.com has attracted so much hype that some enterprising users are creating bots to buy hundreds of items within seconds, which you’ve decided isn’t good for the long-term health of your hat business.

Now that you’ve seen how to expire keys, let’s put it to use on the backend of PyHats.com.

We’re going to create a new Redis client that acts as a consumer (or watcher) and processes a stream of incoming IP addresses, which in turn may come from multiple HTTPS connections to the website’s server.

The watcher’s goal is to monitor a stream of IP addresses from multiple sources, keeping an eye out for a flood of requests from a single address within a suspiciously short amount of time.

Some middleware on the website server pushes all incoming IP addresses into a Redis list with .lpush() . Here’s a crude way of mimicking some incoming IPs, using a fresh Redis database:

>>> r = redis.Redis(db=5)

>>> r.lpush("ips", "51.218.112.236")

1

>>> r.lpush("ips", "90.213.45.98")

2

>>> r.lpush("ips", "115.215.230.176")

3

>>> r.lpush("ips", "51.218.112.236")

4

As you can see, .lpush() returns the length of the list after the push operation succeeds. Each call of .lpush() puts the IP at the beginning of the Redis list that is keyed by the string "ips" .

In this simplified simulation, the requests are all technically from the same client, but you can think of them as potentially coming from many different clients and all being pushed to the same database on the same Redis server.

Now, open up a new shell tab or window and launch a new Python REPL. In this shell, you’ll create a new client that serves a very different purpose than the rest, which sits in an endless while True loop and does a blocking left-pop BLPOP call on the ips list, processing each address:

1# New shell window or tab

2

3import datetime

4import ipaddress

5

6import redis

7

8# Where we put all the bad egg IP addresses

9blacklist = set()

10MAXVISITS = 15

11

12ipwatcher = redis.Redis(db=5)

13

14while True:

15 _, addr = ipwatcher.blpop("ips")

16 addr = ipaddress.ip_address(addr.decode("utf-8"))

17 now = datetime.datetime.utcnow()

18 addrts = f"{addr}:{now.minute}"

19 n = ipwatcher.incrby(addrts, 1)

20 if n >= MAXVISITS:

21 print(f"Hat bot detected!: {addr}")

22 blacklist.add(addr)

23 else:

24 print(f"{now}: saw {addr}")

25 _ = ipwatcher.expire(addrts, 60)

Let’s walk through a few important concepts.

The ipwatcher acts like a consumer, sitting around and waiting for new IPs to be pushed on the "ips" Redis list. It receives them as bytes , such as b”51.218.112.236”, and makes them into a more proper address object with the ipaddress module:

15_, addr = ipwatcher.blpop("ips")

16addr = ipaddress.ip_address(addr.decode("utf-8"))

Then you form a Redis string key using the address and minute of the hour at which the ipwatcher saw the address, incrementing the corresponding count by 1 and getting the new count in the process:

17now = datetime.datetime.utcnow()

18addrts = f"{addr}:{now.minute}"

19n = ipwatcher.incrby(addrts, 1)

If the address has been seen more than MAXVISITS , then it looks as if we have a PyHats.com web scraper on our hands trying to create the next tulip bubble. Alas, we have no choice but to give this user back something like a dreaded 403 status code.

We use ipwatcher.expire(addrts, 60) to expire the (address minute) combination 60 seconds from when it was last seen. This is to prevent our database from becoming clogged up with stale one-time page viewers.

If you execute this code block in a new shell, you should immediately see this output:

2019-03-11 15:10:41.489214: saw 51.218.112.236

2019-03-11 15:10:41.490298: saw 115.215.230.176

2019-03-11 15:10:41.490839: saw 90.213.45.98

2019-03-11 15:10:41.491387: saw 51.218.112.236

The output appears right away because those four IPs were sitting in the queue-like list keyed by "ips" , waiting to be pulled out by our ipwatcher . Using .blpop() (or the BLPOP command) will block until an item is available in the list, then pops it off. It behaves like Python’s Queue.get() , which also blocks until an item is available.

Besides just spitting out IP addresses, our ipwatcher has a second job. For a given minute of an hour (minute 1 through minute 60), ipwatcher will classify an IP address as a hat-bot if it sends 15 or more GET requests in that minute.

Switch back to your first shell and mimic a page scraper that blasts the site with 20 requests in a few milliseconds:

for _ in range(20):

r.lpush("ips", "104.174.118.18")

Finally, toggle back to the second shell holding ipwatcher , and you should see an output like this:

2019-03-11 15:15:43.041363: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.042027: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.042598: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.043143: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.043725: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.044244: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.044760: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.045288: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.045806: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.046318: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.046829: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.047392: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.047966: saw 104.174.118.18

2019-03-11 15:15:43.048479: saw 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Hat bot detected!: 104.174.118.18

Now, Ctrl +C out of the while True loop and you’ll see that the offending IP has been added to your blacklist:

>>> blacklist

{IPv4Address('104.174.118.18')}

Can you find the defect in this detection system? The filter checks the minute as .minute rather than the last 60 seconds (a rolling minute). Implementing a rolling check to monitor how many times a user has been seen in the last 60 seconds would be trickier. There’s a crafty solution using using Redis’ sorted sets at ClassDojo. Josiah Carlson’s Redis in Action also presents a more elaborate and general-purpose example of this section using an IP-to-location cache table.

Persistence and Snapshotting

One of the reasons that Redis is so fast in both read and write operations is that the database is held in memory (RAM) on the server. However, a Redis database can also be stored (persisted) to disk in a process called snapshotting. The point behind this is to keep a physical backup in binary format so that data can be reconstructed and put back into memory when needed, such as at server startup.

You already enabled snapshotting without knowing it when you set up basic configuration at the beginning of this tutorial with the save tùy chọn:

# /etc/redis/6379.conf

port 6379

daemonize yes

save 60 1

bind 127.0.0.1

tcp-keepalive 300

dbfilename dump.rdb

dir ./

rdbcompression yes

The format is save <seconds> <changes> . This tells Redis to save the database to disk if both the given number of seconds and number of write operations against the database occurred. In this case, we’re telling Redis to save the database to disk every 60 seconds if at least one modifying write operation occurred in that 60-second timespan. This is a fairly aggressive setting versus the sample Redis config file, which uses these three save directives:

# Default redis/redis.conf

save 900 1

save 300 10

save 60 10000

An RDB snapshot is a full (rather than incremental) point-in-time capture of the database. (RDB refers to a Redis Database File.) We also specified the directory and file name of the resulting data file that gets written:

# /etc/redis/6379.conf

port 6379

daemonize yes

save 60 1

bind 127.0.0.1

tcp-keepalive 300

dbfilename dump.rdb

dir ./

rdbcompression yes

This instructs Redis to save to a binary data file called dump.rdb in the current working directory of wherever redis-server was executed from:

$ file -b dump.rdb

data

You can also manually invoke a save with the Redis command BGSAVE :

127.0.0.1:6379> BGSAVE

Background saving started

The “BG” in BGSAVE indicates that the save occurs in the background. This option is available in a redis-py method as well:

>>> r.lastsave() # Redis command: LASTSAVE

datetime.datetime(2019, 3, 10, 21, 56, 50)

>>> r.bgsave()

True

>>> r.lastsave()

datetime.datetime(2019, 3, 10, 22, 4, 2)

This example introduces another new command and method, .lastsave() . In Redis, it returns the Unix timestamp of the last DB save, which Python gives back to you as a datetime vật. Above, you can see that the r.lastsave() result changes as a result of r.bgsave() .

r.lastsave() will also change if you enable automatic snapshotting with the save configuration option.

To rephrase all of this, there are two ways to enable snapshotting:

- Explicitly, through the Redis command

BGSAVEorredis-pymethod.bgsave() - Implicitly, through the

saveconfiguration option (which you can also set with.config_set()inredis-py)

RDB snapshotting is fast because the parent process uses the fork() system call to pass off the time-intensive write to disk to a child process, so that the parent process can continue on its way. This is what the background in BGSAVE refers to.

There’s also SAVE (.save() in redis-py ), but this does a synchronous (blocking) save rather than using fork() , so you shouldn’t use it without a specific reason.

Even though .bgsave() occurs in the background, it’s not without its costs. The time for fork() itself to occur can actually be substantial if the Redis database is large enough in the first place.

If this is a concern, or if you can’t afford to miss even a tiny slice of data lost due to the periodic nature of RDB snapshotting, then you should look into the append-only file (AOF) strategy that is an alternative to snapshotting. AOF copies Redis commands to disk in real time, allowing you to do a literal command-based reconstruction by replaying these commands.

Serialization Workarounds

Let’s get back to talking about Redis data structures. With its hash data structure, Redis in effect supports nesting one level deep:

127.0.0.1:6379> hset mykey field1 value1

The Python client equivalent would look like this:

r.hset("mykey", "field1", "value1")

Here, you can think of "field1": "value1" as being the key-value pair of a Python dict, {"field1": "value1"} , while mykey is the top-level key:

| Redis Command | Pure-Python Equivalent |

|---|---|

r.set("key", "value") | r = {"key": "value"} |

r.hset("key", "field", "value") | r = {"key": {"field": "value"}} |

But what if you want the value of this dictionary (the Redis hash) to contain something other than a string, such as a list or nested dictionary with strings as values?

Here’s an example using some JSON-like data to make the distinction clearer:

restaurant_484272 = {

"name": "Ravagh",

"type": "Persian",

"address": {

"street": {

"line1": "11 E 30th St",

"line2": "APT 1",

},

"city": "New York",

"state": "NY",

"zip": 10016,

}

}

Say that we want to set a Redis hash with the key 484272 and field-value pairs corresponding to the key-value pairs from restaurant_484272 . Redis does not support this directly, because restaurant_484272 is nested:

>>> r.hmset(484272, restaurant_484272)

Traceback (most recent call last):

# ...

redis.exceptions.DataError: Invalid input of type: 'dict'.

Convert to a byte, string or number first.

You can in fact make this work with Redis. There are two different ways to mimic nested data in redis-py and Redis:

- Serialize the values into a string with something like

json.dumps() - Use a delimiter in the key strings to mimic nesting in the values

Let’s take a look at an example of each.

Option 1:Serialize the Values Into a String

You can use json.dumps() to serialize the dict into a JSON-formatted string:

>>> import json

>>> r.set(484272, json.dumps(restaurant_484272))

True

If you call .get() , the value you get back will be a bytes object, so don’t forget to deserialize it to get back the original object. json.dumps() and json.loads() are inverses of each other, for serializing and deserializing data, respectively:

>>> from pprint import pprint

>>> pprint(json.loads(r.get(484272)))

{'address': {'city': 'New York',

'state': 'NY',

'street': '11 E 30th St',

'zip': 10016},

'name': 'Ravagh',

'type': 'Persian'}

This applies to any serialization protocol, with another common choice being yaml :

>>> import yaml # python -m pip install PyYAML

>>> yaml.dump(restaurant_484272)

'address: {city: New York, state: NY, street: 11 E 30th St, zip: 10016}\nname: Ravagh\ntype: Persian\n'

No matter what serialization protocol you choose to go with, the concept is the same:you’re taking an object that is unique to Python and converting it to a bytestring that is recognized and exchangeable across multiple languages.

Option 2:Use a Delimiter in Key Strings

There’s a second option that involves mimicking “nestedness” by concatenating multiple levels of keys in a Python dict . This consists of flattening the nested dictionary through recursion, so that each key is a concatenated string of keys, and the values are the deepest-nested values from the original dictionary. Consider our dictionary object restaurant_484272 :

restaurant_484272 = {

"name": "Ravagh",

"type": "Persian",

"address": {

"street": {

"line1": "11 E 30th St",

"line2": "APT 1",

},

"city": "New York",

"state": "NY",

"zip": 10016,

}

}

We want to get it into this form:

{

"484272:name": "Ravagh",

"484272:type": "Persian",

"484272:address:street:line1": "11 E 30th St",

"484272:address:street:line2": "APT 1",

"484272:address:city": "New York",

"484272:address:state": "NY",

"484272:address:zip": "10016",

}

That’s what setflat_skeys() below does, with the added feature that it does inplace .set() operations on the Redis instance itself rather than returning a copy of the input dictionary:

1from collections.abc import MutableMapping

2

3def setflat_skeys(

4 r: redis.Redis,

5 obj: dict,

6 prefix: str,

7 delim: str = ":",

8 *,

9 _autopfix=""

10) -> None:

11 """Flatten `obj` and set resulting field-value pairs into `r`.

12

13 Calls `.set()` to write to Redis instance inplace and returns None.

14

15 `prefix` is an optional str that prefixes all keys.

16 `delim` is the delimiter that separates the joined, flattened keys.

17 `_autopfix` is used in recursive calls to created de-nested keys.

18

19 The deepest-nested keys must be str, bytes, float, or int.

20 Otherwise a TypeError is raised.

21 """

22 allowed_vtypes = (str, bytes, float, int)

23 for key, value in obj.items():

24 key = _autopfix + key

25 if isinstance(value, allowed_vtypes):

26 r.set(f"{prefix}{delim}{key}", value)

27 elif isinstance(value, MutableMapping):

28 setflat_skeys(

29 r, value, prefix, delim, _autopfix=f"{key}{delim}"

30 )

31 else:

32 raise TypeError(f"Unsupported value type: {type(value)}")

The function iterates over the key-value pairs of obj , first checking the type of the value (Line 25) to see if it looks like it should stop recursing further and set that key-value pair. Otherwise, if the value looks like a dict (Line 27), then it recurses into that mapping, adding the previously seen keys as a key prefix (Line 28).

Let’s see it at work:

>>>>>> r.flushdb() # Flush database: clear old entries

>>> setflat_skeys(r, restaurant_484272, 484272)

>>> for key in sorted(r.keys("484272*")): # Filter to this pattern

... print(f"{repr(key):35}{repr(r.get(key)):15}")

...

b'484272:address:city' b'New York'

b'484272:address:state' b'NY'

b'484272:address:street:line1' b'11 E 30th St'

b'484272:address:street:line2' b'APT 1'

b'484272:address:zip' b'10016'

b'484272:name' b'Ravagh'

b'484272:type' b'Persian'

>>> r.get("484272:address:street:line1")

b'11 E 30th St'

The final loop above uses r.keys("484272*") , where "484272*" is interpreted as a pattern and matches all keys in the database that begin with "484272" .

Notice also how setflat_skeys() calls just .set() rather than .hset() , because we’re working with plain string:string field-value pairs, and the 484272 ID key is prepended to each field string.

Encryption

Another trick to help you sleep well at night is to add symmetric encryption before sending anything to a Redis server. Consider this as an add-on to the security that you should make sure is in place by setting proper values in your Redis configuration. The example below uses the cryptography package:

$ python -m pip install cryptography

To illustrate, pretend that you have some sensitive cardholder data (CD) that you never want to have sitting around in plaintext on any server, no matter what. Before caching it in Redis, you can serialize the data and then encrypt the serialized string using Fernet:

>>>>>> import json

>>> from cryptography.fernet import Fernet

>>> cipher = Fernet(Fernet.generate_key())

>>> info = {

... "cardnum": 2211849528391929,

... "exp": [2020, 9],

... "cv2": 842,

... }

>>> r.set(

... "user:1000",

... cipher.encrypt(json.dumps(info).encode("utf-8"))

... )

>>> r.get("user:1000")

b'gAAAAABcg8-LfQw9TeFZ1eXbi' # ... [truncated]

>>> cipher.decrypt(r.get("user:1000"))

b'{"cardnum": 2211849528391929, "exp": [2020, 9], "cv2": 842}'

>>> json.loads(cipher.decrypt(r.get("user:1000")))

{'cardnum': 2211849528391929, 'exp': [2020, 9], 'cv2': 842}

Because info contains a value that is a list , you’ll need to serialize this into a string that’s acceptable by Redis. (You could use json , yaml , or any other serialization for this.) Next, you encrypt and decrypt that string using the cipher vật. You need to deserialize the decrypted bytes using json.loads() so that you can get the result back into the type of your initial input, a dict .

Lưu ý :Fernet uses AES 128 encryption in CBC mode. See the cryptography docs for an example of using AES 256. Whatever you choose to do, use cryptography , not pycrypto (imported as Crypto ), which is no longer actively maintained.

If security is paramount, encrypting strings before they make their way across a network connection is never a bad idea.

Compression

One last quick optimization is compression. If bandwidth is a concern or you’re cost-conscious, you can implement a lossless compression and decompression scheme when you send and receive data from Redis. Here’s an example using the bzip2 compression algorithm, which in this extreme case cuts down on the number of bytes sent across the connection by a factor of over 2,000:

>>> 1>>> import bz2

2

3>>> blob = "i have a lot to talk about" * 10000

4>>> len(blob.encode("utf-8"))

5260000

6

7>>> # Set the compressed string as value

8>>> r.set("msg:500", bz2.compress(blob.encode("utf-8")))

9>>> r.get("msg:500")

10b'BZh91AY&SY\xdaM\x1eu\x01\x11o\x91\x80@\x002l\x87\' # ... [truncated]

11>>> len(r.get("msg:500"))

12122

13>>> 260_000 / 122 # Magnitude of savings

142131.1475409836066

15

16>>> # Get and decompress the value, then confirm it's equal to the original

17>>> rblob = bz2.decompress(r.get("msg:500")).decode("utf-8")

18>>> rblob == blob

19True

The way that serialization, encryption, and compression are related here is that they all occur client-side. You do some operation on the original object on the client-side that ends up making more efficient use of Redis once you send the string over to the server. The inverse operation then happens again on the client side when you request whatever it was that you sent to the server in the first place.

Using Hiredis

It’s common for a client library such as redis-py to follow a protocol in how it is built. In this case, redis-py implements the REdis Serialization Protocol, or RESP.

Part of fulfilling this protocol consists of converting some Python object in a raw bytestring, sending it to the Redis server, and parsing the response back into an intelligible Python object.

For example, the string response “OK” would come back as "+OK\r\n" , while the integer response 1000 would come back as ":1000\r\n" . This can get more complex with other data types such as RESP arrays.

A parser is a tool in the request-response cycle that interprets this raw response and crafts it into something recognizable to the client. redis-py ships with its own parser class, PythonParser , which does the parsing in pure Python. (See .read_response() if you’re curious.)

However, there’s also a C library, Hiredis, that contains a fast parser that can offer significant speedups for some Redis commands such as LRANGE . You can think of Hiredis as an optional accelerator that it doesn’t hurt to have around in niche cases.

All that you have to do to enable redis-py to use the Hiredis parser is to install its Python bindings in the same environment as redis-py :

$ python -m pip install hiredis

What you’re actually installing here is hiredis-py , which is a Python wrapper for a portion of the hiredis C library.

The nice thing is that you don’t really need to call hiredis bản thân bạn. Just pip install it, and this will let redis-py see that it’s available and use its HiredisParser instead of PythonParser .

Internally, redis-py will attempt to import hiredis , and use a HiredisParser class to match it, but will fall back to its PythonParser instead, which may be slower in some cases:

# redis/utils.py

try:

import hiredis

HIREDIS_AVAILABLE = True

except ImportError:

HIREDIS_AVAILABLE = False

# redis/connection.py

if HIREDIS_AVAILABLE:

DefaultParser = HiredisParser

else:

DefaultParser = PythonParser

Using Enterprise Redis Applications

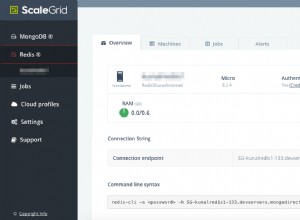

While Redis itself is open-source and free, several managed services have sprung up that offer a data store with Redis as the core and some additional features built on top of the open-source Redis server:

-

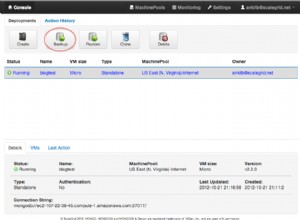

Amazon ElastiCache for Redis : This is a web service that lets you host a Redis server in the cloud, which you can connect to from an Amazon EC2 instance. For full setup instructions, you can walk through Amazon’s ElastiCache for Redis launch page.

-

Microsoft’s Azure Cache for Redis : This is another capable enterprise-grade service that lets you set up a customizable, secure Redis instance in the cloud.

The designs of the two have some commonalities. You typically specify a custom name for your cache, which is embedded as part of a DNS name, such as demo.abcdef.xz.0009.use1.cache.amazonaws.com (AWS) or demo.redis.cache.windows.net (Azure).

Once you’re set up, here are a few quick tips on how to connect.

From the command line, it’s largely the same as in our earlier examples, but you’ll need to specify a host with the h flag rather than using the default localhost. For Amazon AWS , execute the following from your instance shell:

$ export REDIS_ENDPOINT="demo.abcdef.xz.0009.use1.cache.amazonaws.com"

$ redis-cli -h $REDIS_ENDPOINT

For Microsoft Azure , you can use a similar call. Azure Cache for Redis uses SSL (port 6380) by default rather than port 6379, allowing for encrypted communication to and from Redis, which can’t be said of TCP. All that you’ll need to supply in addition is a non-default port and access key:

$ export REDIS_ENDPOINT="demo.redis.cache.windows.net"

$ redis-cli -h $REDIS_ENDPOINT -p 6380 -a <primary-access-key>

The -h flag specifies a host, which as you’ve seen is 127.0.0.1 (localhost) by default.

When you’re using redis-py in Python, it’s always a good idea to keep sensitive variables out of Python scripts themselves, and to be careful about what read and write permissions you afford those files. The Python version would look like this:

>>> import os

>>> import redis

>>> # Specify a DNS endpoint instead of the default localhost

>>> os.environ["REDIS_ENDPOINT"]

'demo.abcdef.xz.0009.use1.cache.amazonaws.com'

>>> r = redis.Redis(host=os.environ["REDIS_ENDPOINT"])

Thats tất cả để có nó. Besides specifying a different host , you can now call command-related methods such as r.get() as normal.

Lưu ý :If you want to use solely the combination of redis-py and an AWS or Azure Redis instance, then you don’t really need to install and make Redis itself locally on your machine, since you don’t need either redis-cli or redis-server .

If you’re deploying a medium- to large-scale production application where Redis plays a key role, then going with AWS or Azure’s service solutions can be a scalable, cost-effective, and security-conscious way to operate.

Wrapping Up

That concludes our whirlwind tour of accessing Redis through Python, including installing and using the Redis REPL connected to a Redis server and using redis-py in real-life examples. Here’s some of what you learned:

redis-pylets you do (almost) everything that you can do with the Redis CLI through an intuitive Python API.- Mastering topics such as persistence, serialization, encryption, and compression lets you use Redis to its full potential.

- Redis transactions and pipelines are essential parts of the library in more complex situations.

- Enterprise-level Redis services can help you smoothly use Redis in production.

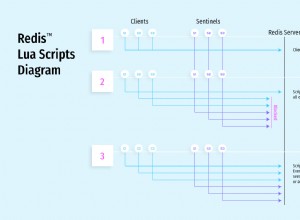

Redis has an extensive set of features, some of which we didn’t really get to cover here, including server-side Lua scripting, sharding, and master-slave replication. If you think that Redis is up your alley, then make sure to follow developments as it implements an updated protocol, RESP3.

Further Reading

Here are some resources that you can check out to learn more.

Books:

- Josiah Carlson: Redis in Action

- Karl Seguin: The Little Redis Book

- Luc Perkins et. al.: Seven Databases in Seven Weeks

Redis in use:

- Twitter: Real-Time Delivery Architecture at Twitter

- Spool: Redis bitmaps – Fast, easy, realtime metrics

- 3scale: Having fun with Redis Replication between Amazon and Rackspace

- Instagram: Storing hundreds of millions of simple key-value pairs in Redis

- Craigslist: Redis Sharding at Craigslist

- Disqus: Redis at Disqus

Other:

- Digital Ocean: How To Secure Your Redis Installation

- AWS: ElastiCache for Redis User Guide

- Microsoft: Azure Cache for Redis

- Cheatography: Redis Cheat Sheet

- ClassDojo: Better Rate Limiting With Redis Sorted Sets

- antirez (Salvatore Sanfilippo): Redis persistence demystified

- Martin Kleppmann: How to do distributed locking

- HighScalability: 11 Common Web Use Cases Solved in Redis